Robert Seatter on poetry and place making

Chair of the Poetry Archive Robert Seatter has recently been Poet in Residence at two very special places – Sir John Soane’s Museum in central London, an extraordinary 19th century cabinet of curiosities, and Kelmscott Manor in Oxfordshire, the ‘heaven on earth’ home of artist and writer William Morris, which inspired many of Morris’s most celebrated designs. Here he reflects on the power of poetry to bring these unique places to life.

What is a Poet in Residence? This is the question that everyone usually asks me straight off. I think they envisage me living in a chi-chi historic apartment or else roving the residence as a cross between a tour guide and a ghost in the attic! Of course, it’s neither of these. Usually, it’s based on a fascination with a certain place – that then leads to a request for special access, to invaluable time with knowledgeable curators, and to access to some of their unique archives and artefacts.

And then the rest is – wonderfully, usually – left to you. What inspires you; what is extraordinary (or ordinary), revelatory and strange about this place; and what is its relevance to the present moment…

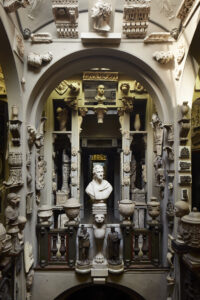

The object-filled space of Sir John Soane’s Museum.

Write my story!

How to begin? is often the next question. And that is an obvious one when faced with the 50,000 objects that are crammed into Sir John Soane’s Museum. So I walked its labyrinthine corridors, almost as a stranger again, and just selected the objects and spaces that intrigued me most, that shouted loudest at me: Write my story! With Soane, it was his star object, the alabaster sarcophagus of Seti I, lodged at the bottom of the house, that demanded an immediate incantation:

Like a boat left in a room,

waiting for a door to let in a river,

for a current and for a paddle…

‘Sarcophagus’

At Kelmscott Manor, its sometime resident William Morris, indicated the way to go… He himself wrote a poem for his bed, which was then embroidered around the pelmet – almost as if he were giving me permission to follow his lead. So I did just that, creating a trail of ten poems through the various spaces, each one bringing an object to life, and recorded onto a very 21st century app. My new poem for the bed begins:

I am for lying on in the winter time,

for a sleep as deep as hibernation…

‘Bed’

William Morris’s bed with poem around its pelmet, Kelmscott Manor.

Sometimes the objects I chose speak – like the Bed – in their own words: a wall hanging, designed and embroidered by William and his wife Jane Morris, articulates the complex harmony of their marriage; a wallpaper catches the reiteration of memory; a dark green paint colour evokes Morris’s passion for nature; and sometimes the people themselves reflect on their own past lives, as in Rossetti’s ravishing portrait of Jane Morris where Jane steps out of her portrait to interrogate the portrayal of her:

No,

the blue silk dress was his idea, his idea

of me, in the afternoons when I lay with him,

that thrilling looseness of gushing cloth –

like the river round this house…

‘The Blue Silk Dress’

The Blue Silk Dress, portrait by Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Promenade poetry

The trail through Sir John Soane’s Museum was led memorably in person by candle light – once a month visitors crowd into its narrow spaces to catch the emotive stories of its inhabitants and the strange history of its objects. Poetry focusses the moment…

Objects given voice there included the central protagonist of Hogarth’s The Rake’s Progress (which hangs in the Museum and offers an uncanny resemblance to Soane’s own wayward son); the cantilevered staircase in the Museum’s hallway that seems to float in air; and the miniature model of the tomb that Soane designed for his beloved wife, which extraordinarily became the inspiration for the famous red London telephone box designed in the 1920s by Giles Gilbert Scott – a perfect poetic conflation!:

I am a tomb

I am a telephone box

I am dead

I am calling

from the other side

‘Mrs Soane’s Tomb becomes a Telephone Box’

And there are further encounters with the contemporary. The polar opposite of Soane the obsessive collector of the 19th century would be the living artist Michael Landy who famously destroyed all his possessions. I imagine a conversation between the two of them:

Do you ever dream of an empty house…

walking out of it,

yourself on an empty road,

carrying nothing but the clothes on your back,

listening to the sound of your breath –

how the horizon lifts

and trembles…?

‘The Man who destroyed everything he had meets Sir John Soane’

Similarly in Kelmscott, I imagine William Morris meeting the iconoclastic artist Grayson Perry in a game of poetic ‘consequences’.

Capturing the universal

Beyond specific objects and artefacts, there are broader themes that surface out of the these places, that capture the universal. In Soane’s case, it was this obsession for ‘stuff’, his need to define himself through a never-ending quest for objects:

Everything must go in… Everything,

everything. Now recite the list of what you

saved. Now the one thing you missed:

its gleaming plinth, its jealous empty space.

‘The House of Everything’

And we are all in a little way like Soane – using objects and spaces as our repositories of memory, as ways of defining who we are.

In Kelmscott Manor, it was William Morris’s passion for ‘making’, his deep-seated belief that all of us are ‘makers’ and that we all need things that are useful and beautiful in our lives, that surfaced from my time there. Doing this residency a few years after the pandemic, I recognized how strongly so many of us have re-found this impulse:

…of holding time in one’s hand –

its texture, warp and weft, fresh colour

on the fingers – and of saying

stop for just a second:

here it is.

‘The House of Making’

I also explored Morris as a symbol of Englishness, in a post-Brexit world, torn between an attraction for the past and the desperate need to embrace a new future…

Of dreams so keen

they will keep us awake, and this house

like a boat set free on the tide.

‘Albion’

The memorable façade of Kelmscott Manor.

Public engagement

Both these residencies gave me wonderful opportunities to explore my own personal creativity but they were also just as importantly about inspiring that in others.

So I worked with visitors to the Museum and the Manor to help them express what these spaces meant to them. In Kelmscott, this grew into a whole Summer of Creativity, with simple engagement triggers at key points around the house (Write three words that define the Manor/Write a goodbye message/Draw your favourite object/Write in its voice etc). It included an inspiring collaboration with visual artist Jessica Palmer, and will culminate in a giant community poem for National Poetry Day in October 2025.

A last word – in the appropriately titled poem Coda – is about what these spaces come to mean to us in our lives. Yes, how they fascinate and intrigue us in the moment, but more profoundly how they become part of who we are. Many visitors told me this, and it is so for me too. That thought is captured here, in the last poem of The House of Everything:

So this is who I was and am,

this house seems to say, and perhaps will be.

‘Coda’

Entrance hall of Sir John Soane’s Museum.

The poetry collections published from these two residencies are: The House of Everything (Seren), The House of Words (Paekakiriki Press). Further information here: www.robertseatter.co.uk

With thanks to both the Sir John Soane’s Museum and Kelmscott Manor for their kind permission to use these photos.